Archive for the ‘Video Shooter (Book)’ Category

Use Broad Lighting to Increase Three-Dimensionality

Use Broad Lighting to Increase Three-Dimensionality

As filmmakers and directors of photography, we are constantly working to recreate the 3D world in a 2D medium. We use a variety of techniques to accomplish this, for example, by maximizing the use of linear perspective, and when blocking actors, by placing one slightly behind the other. For the same reason, when lighting scenes, we aim to maximize texture, by carefully crafting the direction and character of the light as manifested in the shadows and highlights. Broad lighting can also help foster the (usually) desired three-dimensional illusion, by imparting a natural wraparound texture, especially in the hair and side of the face of female talent. The Rosco LitePad Vector CCT is particularly effective in this regard, given today’s ultra-sensitive, high dynamic range cameras.

The diminutive 8-inch x 8-inch LitePad is ruggedly manufactured and offers much better than average performance, especially in the tungsten wavelengths where many LEDs tend to struggle. The light’s output, while somewhat less than the larger, more common 1 x 1 units on the market, is ideal as a wraparound luminaire when shooting talking-heads, or in a dark car at night.

The LitePad Vector CCT LED is especially well-suited as a side or backlight for interviews and standups.

The Vector Litepad exhibits good red saturation produces very smooth skin tones, an imperative for shooters these days working exclusively with LED lighting.

Shooting In log Makes Sense For Most Shooters

Shooting In log Makes Sense For Most Shooters

We all know that shooting in log can improve exposure latitude and dynamic range. In short, log capture allows us to record more professional-looking images, as the brightest highlights in sun-dappled scenes, for example, may often be accommodated without clipping or loss of detail.

Practically, shooting in log may also mean utilizing less fill light, which can be helpful on low-budget run-and-gun style productions. I always try to reduce the amount of gear in general on a set; and shooting in log can help reduce the grip and lighting complement substantially – a good thing in my opinion.

Remember more gear = less work.

Giving you an idea of how I work in log, when shooting with the VariCam LT, for example, I assign Y-Get to user button 1. Placing the EVF cross-hairs over the brightest part of a scene, with the iris adjusted to 69 IRE, the camera recording V-Log will accommodate 3-4 stops of additional latitude before clipping or a noticeable loss of highlight detail. Setting exposure in this way is simple and effective, and eliminates the need for external exposure meters and pricey reference monitors.

While shooting in log makes sense for most shooters, broadcast news and some non-fiction shooters may find the hassle and inconvenience of working with LUTs not be worth it, or even possible, given the tight time constraints and lack of serious post-production in most news and public affairs programming.

This scene captured in log is shown with and without a LUT applied. Despite the advantages of shooting in log, some producers may see working with LUTs as a hassle and an inconvenience.

Offloading Huge Camera Files Over Time

Offloading Huge Camera Files Over Time

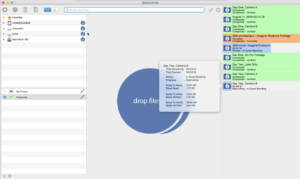

Since the advent of tapeless workflows it has been necessary to safely and securely offload camera original footage from memory cards and onboard drives. For many of us this can be a process fraught with trepidation, which is why I and most industry professionals use Imagine Products’ ShotPut Pro to handle the offloading chore.

Of course we need an effective checksum to verify the integrity of the transfer and SPP has done that very well for almost a decade. In that regard ShotPut Pro version 6 retains the key checksum options from fastest to slowest; most data wranglers I know will opt for XXHASH (the fastest option) or MD5.

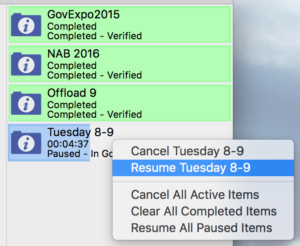

One valuable new feature in ShotPut Pro’s latest version is the PAUSE & RESUME function since on so many productions these days we are pressed for time and forced to interrupt the transfer of large data files. On many shows there are simply not enough hours in a day to permit the uninterrupted offload of the gargantuan 4K and higher resolution camera files.

Provided that the application is not closed or quit, SPP6 will resume and complete the transfer of large files without reinitiating the entire transfer. SPP6 completes the immediate file in progress so it does not truncate or interrupt a file prior to pausing or interrupting the transfer.

How many times have we been forced to move from hotel room to a moving vehicle and into a new hotel room while attempting to offload large camera drives and media cards? Shotput Pro 6 addresses the needs of frazzled data wranglers in precisely this unenviable position.

ShotPut Pro 6’s new PAUSE & RESUME feature enables users to interrupt a long data-heavy offload for completion later. This ability to transfer large files in intervals is long overdue!

My Upcoming Workshop at Portland’s Cool Film Festival

My Upcoming Workshop at Portland’s Cool Film Festival

This year I am pleased and honored to be conducting a three-day camera and visual storytelling workshop at PDXFF16. This fun hands-on event will take place from August 31 – September 2 at the Pro Photo Event Center in the city’s NW Pearl District, 1801 NW Northrup Ave, Portland OR 97209.

While the workshop is designed primarily for aspiring camera craftsmen and cinematographers the course is just as applicable to filmmakers of every stripe, including actors and screenwriters, and visual storytellers of all media.

For more information and to register click on the general festival link:[www.portlandfilm.org] and the event specific link: [https://www.eventbrite.com/e/professional-camera-visual-storytelling-tickets-26573603363]

Scene: London Film School Camera Workshop 2015

Road to Zanzibar

Road to Zanzibar

This summer I am again in East Africa leading a camera and visual storytelling workshop at the Zanzibar International Film Festival. The hunger for knowledge in this part of the world never ceases to amaze me as my students demonstrate an eagerness to learn and practice the fundamental lessons of good visual storytelling and effective camera operation.

Zanzibar is located off the coast of East Africa at 6º south latitude. The light at dusk is positively mesmerizing. Here a traditional dhow passes off the coast of Stone Town 8 July 2016.

Despite the technical challenges DSLR cameras dominate the filmmaking landscape in this part of the world.

The opportunity to integrate a range of local color is a great advantage of shooting in Zanzibar.

Lulu. The star of our scenario. In real life she is a popular fashion model.

The emphasis of local cinema is on actors and performance which is as it should be. Technical issues aside it is after all what audiences really care about.

3D MAY BE ALL BUT DEAD BUT THE CRAFT LESSONS OF 3D ARE NOT

3D MAY BE ALL BUT DEAD BUT THE CRAFT LESSONS OF 3D ARE NOT

Its most recent demise has been nothing short of astonishing. As recently as four years ago 3D seemed atop of the world and gaining momentum with filmmakers and TV broadcasters around the world seemingly poised to jump on the 3D bandwagon. Pouring tens of millions of dollars into new cameras, rigs, and displays, the major manufacturers like Sony and Panasonic subsidized to a huge extent startup venues like Sky 3D and Direct TV’s Channel 101. By January 2013 virtually every large screen display sold in the USA offered a 3D capability.

Then what happened? Despite the manufacturers’ best efforts and massive financial investment the public in Western countries never really cared for 3D. In Asia the public’s view was more positive but the interaxial handwriting was already on the wall in the principal markets in the USA and Europe.

Today, save for the few studio tentpole movies still distributed in 3D, the format has become all but irrelevant for most non-theatrical applications. You can blame it on the uncomfortable glasses, the underpowered insufficiently bright displays, or the poorly developed skills of 3D filmmakers, who not understanding the physiological impact of stereo viewing, unwisely opted for maximize depth at the price of viewer comfort. It goes without saying that inflicting riveting pain on one’s audience is not a good way to win its loyalty and affection!

Since the dawn of painting and photography the challenge to artiss has always been how to best represent the 3D world in a 2D medium. Because the world we live in has depth and dimension, our filmic universe is usually expected to reflect this quality by presenting the most life-like three-dimensional illusion possible for our screen characters to live, breathe and operate most transparently.

In the 2D world of cinema and TV the camera craftsman uses mainly texture and perspective to foster the desired three-dimensional illusion. While the 3D shooter makes use of many of the same tools the stereo format inherently goes a long way to promote the feeling of a real world experience. In fact the 3D shooter must often mitigate the use of aggressive depth cues, as the forcing of perspective can be very painful to viewers.

As a cinematographer and 3D specialist I attribute the format’s lack of public acceptance to something rather fundamental. Of course the ‘3D’ format isn’t really 3D at all but stereo, which is much less immersive. Viewing a movie or TV broadcast in stereo requires substantial viewer effort, a reliance on a gimmick or ‘loophole’ in human physiology that allows viewers to separate focus from convergence. As it turns out a large part of the audience is simply unable or unwilling to perform the unnatural act of forming a 3D image in its mind; it can be tiring or painful, and not at all conducive to what is supposed to be an entertaining experience.

In spite of all this, the savvy cameraperson today understands that the lessons of 3D, i.e. communicating the maximum number of depth cues to viewers, can greatly enhance the impact, breadth, and effectiveness, of our traditionally composed 2D captured scenes.

LUTs for ‘Luttites’

LUTs for ‘Luttites’

On many shows we are increasingly shooting RAW and/or in a multitude of compressed formats with different cameras utilizing different flavors of log. ARRI Alexa, Canon C300, Sony FS7, Panasonic VariCam, GoPro, Blackmagic, DSLRs – just keeping all the color spaces and log profiles straight can be a major challenge.

The Academy Color Encoding System (ACES) has simplified things for folks at the high end of the food chain. But for the rest of us toiling in typical broadcast productions and independent features, the convoluted post-camera wrangling of color and LUTs has become an unwelcome hassle with the wholesale wrangling of .cube, .aml, and .ctl files.

Thankfully we now have Latice, a powerful and versatile LUT management tool that greatly minimizes this ongoing hassle. To be clear it is not intended to compete with or replace grading applications like Davinci Resolve. Think of it more as a LUT Swiss Army Knife, able to view, transcode, and conform, a wide array of color spaces and profiles.

So if you’re shooting B-roll on a Canon C300 Mark II and we need to conform to the A camera which is a Sony FS7, Lattice can convert the Canon Log2 files to Sony S-Log, which we then import into Resolve for simple and straightforward color grading in a single consistent color space.

The Mac-based app features a very straightforward interface, which offers plenty of hooks for tweaking. As cameras like the Panasonic VariCam 35 are enabling the creation of 3D LUTs in camera it becomes a simple matter in Lattice to convert Panasonic’s V-Log file to something else, like Sony S-Log or Blackmagic’s Film Emulation (BMD) LUT.

Lattice doesn’t eliminate entirely the complexity and hassle of wrangling LUTs post-camerabut it sure makes the ordeal a whole lot easier.

I use it regularly and recommend it.

Lattice is a very simple LUT management tool. If you shoot with multiple cameras and employ various color spaces Lattice will conform the different LUT flavors to a single format for grading inside Davinci Resolve (or other color correction environment).

I’m Missing the Connection Here

I’m Missing the Connection Here

The data and power cables poking in and out of my MacBook Pro are pure crap. Take a look at how I’m managing my AC charger cord. I’ve added three cable ties over a sleeve of black camera tape to ensure adequate stress relief and thus forestall the eruption of arcs and sparks from the broken connection.

Why can’t cable manufacturers simply provide sufficient stress relief in the first place?

The matter of diseased trouble-prone cables is not a new phenomenon. After 35 years in the business I know from hard-won experience that 90% of failures in the field are due to defective cables and connectors. Thinking about it now my ARRI 16SR in 1976 was a true godsend. The camera utilized onboard batteries that eliminated completely failure-prone cables and plugs. It gave me great peace of mind that this disproportionate cause of failure was gone forever.

Thunderbolt is an impressive technology and we’ve grown to rely on the less than robust cables for our most critical tasks from off-loading original camera footage to preparing our backup volumes. With data rates up to 40Gbps in Thunderbolt3 the flow of data is sensitive to a range of cable snafus, especially at the point where the cable enters the rigid connector where most failures due to fatigue occur.

For manufacturers, the cost of producing cables with proper stress relief might amount to a few pennies per unit, but as shooters and content creators whose business is capturing, transferring, and managing critical data, the extra dollar or two per cable at retail is worth it, if only to avoid the indignity of having to affix a raft of cable ties simply to ensure a solid and reliable connection.

A cable usually fails at the point it enters the solid connector. Affixing a series of plastic cable ties can provide increased stress relief and help forestall an intermittent connection.

A New Kind of Package Lens

A New Kind of Package Lens

One of the truisms of our profession has long been a camera system is only as good as its optics. While computational non-optical lenses in devices like the iPhone have obviated the need in some applications for finely crafted optics, the demand persists for high-performance glass at the high end of our business, especially in light of the latest 4K and higher resolution cameras.

The new Sony PXW-FS7 4K camcorder is well-balanced and robust, with superb ergonomics. Particularly notable, however, is Sony’s own 28-135mm F4 lens that comes with it. It is not the typical crappy package lens that usually accompanies new mid-range cameras.

Employing precisely sculpted aspheric elements and low-dispersion glass the FS7 4K zoom represents a real breakthrough in economical s35mm lens technology. Remarkably free of chromatic aberrations – the main reason cheap lenses look cheap – the lens compares favorably with much pricier optics; its relatively slow F4 maximum aperture posing less of a challenge these days for shooters employing cameras like the FS7 that shoot virtually noise-free at ISO 2000 and higher.

Sony’s lens uses precise servo control of zoom and focus to enable a constant F-stop throughout the zoom range. Some shooters will object to the limited 5:1 zoom for documentary work but keep in mind the lens is a large format zoom. If you’re looking for a 23x capability you should consider a 2/3-inch camera like the Varicam HS, which is ideal for travel and sports, and certain wildlife titles, that tend to employ long zoom telephoto lenses.

Sony’s new 28-135mm E-mount zoom offers very high performance in an economical S35mm format lens.

The zoom even at maximum magnification is remarkably free of chromatic aberrations.

Exclude! Exclude! Exclude! Takes on New Meaning

Exclude! Exclude! Exclude! Takes on New Meaning

With the advent of cameras like the extreme low-light ISO 5000 Varicam 35 the imperative to exclude, exclude, exclude, unhelpful story elements inside the frame takes on a more dramatic dimension. Shooting with the new Varicam in very low light at night, for example, means that streetlights suddenly appear blown out, the night sky over major cities is way too bright, and the intensity of incidental TV monitor and screens in the background must be substantially reduced.

With the advent of cameras like the extreme low-light ISO 5000 Varicam 35 the imperative to exclude, exclude, exclude, unhelpful story elements inside the frame takes on a more dramatic dimension. Shooting with the new Varicam in very low light at night, for example, means that streetlights suddenly appear blown out, the night sky over major cities is way too bright, and the intensity of incidental TV monitor and screens in the background must be substantially reduced.

This way of working is a revolution in how camera folks have managed the world until now. In the film days of years ago we needed light and plenty of it to gain even a minimum exposure. Moderately sensitive digital cameras like the Alexa of several years ago gave us the freedom to illuminate scenes with smaller low-wattage, more economical, cooler units. A blessing to be sure!

Today given the latest ultra sensitive digital cinema cameras entering the market we are back to spending a lot of time addressing the lighting in our setups, not so much by adding massive hot lights of course, but by employing more extensive lighting control, that is, by taking light away.

Given the new technology my old harangue to students to exclude everything not supportive of the visual story has taken on even greater relevance and urgency.