The Right Interaxial For You

The Right Interaxial For You

It’s not a stupid question. Consider the major strength and weakness of the Panasonic 3DA1 is its orthostereoscopic 60mm interaxial. On the one hand by matching a human being’s interocular distance, we can be assured that objects captured at a “normal” distance with a “normal” lens will appear with a “normal” roundness from a human being’s perspective. This is critical if we as shooters are to be successful in our 3D endeavors: capturing your leading lady or young starlet with her head shaped like a medicine ball will not do much for your career.

On the other hand the 60mm interaxial can be limiting; objects approaching well inside of ten feet (3m) may cause severe eye strain; the hyperconvergence inducing headaches, nausea and a flight to the exits. This is because the converging of the eyes requires musular effort, which increases dramatically with diminishing object distance. A similar peril exists on the other side of the screen in positive space. The 60mm IA increases the risk of hyperconvergence; a condition audiences particularly loathe as they try to splay their eyes out like Marty Feldman.

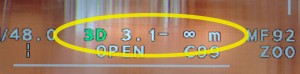

Panasonic’s new 3D camcorder HDC-Z10000 effectively reduces the risk of hyperconvergent and hyperdivergent conditions. By shrinking the interaxial to 42mm the economical 3D model ($3500 list) will allow comfortable capture of objects down to a mere 17 inches (45cm). This means the Z10000 will prove more useful in the critical six to eight foot (1.5m – 2.5m) range where we shooters tend to do most of our work.

The down side of the narrower IA is the noticeable loss of depth beyond fifteen feet (4.5m). This may be fine if working primarily on sets or for shooting sit-down intereviews when coupled with the wider than normal (32mm equivalent) lens. This is a critical point. Shooting with the Z10000 and a “normal” lens will yield the approximate point of view of a small dog or cat whose interocular distance is 42mm. Maybe this is what you want, maybe it isn’t. The point is to know what the heck you are doing: The narrow IA decreases roundness from a human perspective; the wider field of view gained from the 32mm equivalent lens increases roundness to restore the human perspective.

The design of the Z10000 with its lofty ridiculous model number is designed to do exactly that.

Panasonic's Z10000's 42mm interaxial allows comfortable close placement of objects as close as 17 inches (45cm) but beware the loss of the human perspective; we see the world with our eyes about 65mm apart and so our 3D camera and storytelling skills must be adjusted to ensure capturing objects with the proper desired roundness.

Mega Hype Abounds for Canon’s New Camera

Mega Hype Abounds for Canon’s New Camera

Unless you’re Sony it isn’t too often that a camera manufacturer rents a Hollywood studio, in this case Paramount, and hires an A-list director, in this case, Martin Scorsese, to do the introductory honors. But that’s exactly the case on November 3 as Canon will announce its most professional large-format camera yet from its underrated and (until now) ignored video division. Not another DSLR variant, the new camera is expected to offer very high resolution at 4K or greater, 4:2:2 intraframe compression, and practical recording to SSD onboard storage. Any way you look at the new camera, this is an aggressive upscale move, and a veritable shot across the bow to Sony’s best-seller F3 model, which has dominated the scene for most of the past year.

Given Canon’s propensity for excellent controls, rugged construction, and operational ease, this camera could quickly become a major player in the large-sensor camera wars, especially given the quality of Canon optics that will surely go with it. As Panasonic fumbles and Sony shakes in its boots, the stakes couldn’t be greater for the major camera manufacturers (and RED) as we near the moment of the great announcement amid the pomp and circumstance this coming Thursday.

Stay tuned. I’ll be all over this one.

The French are Going 3D – Even If Others Aren’t

The French are Going 3D – Even If Others Aren’t

In a recent poll about 80% of Americans were said to hold a negative view of 3D entertainment movies and TV. With such a predisposition towards 3D it’s not surprising that 3DTV should find very tough going in North America. In Southeast Asia, the 80% figure also applies, except there the lop-sided percentage refers to positive feelings towards three-dimensional format; only 20% of consumers of theatrical fare have a somewhat or very negative view of 3D.

In Europe the feelings are not quite so negative towards 3D entertainment, especially in France, where the bulk of 3D equipment sales, cameras and plasma displays have taken place. I am in the UK this week, and I can perceive a substantial level of resistance from consumers, albeit at not nearly the level of disinterest or even antipathy that is currently the case in the U.S.

Maybe France knows something the rest of the West doesn’t. Or else it may simply be reflective more of French culture and proclivities in the cinema.

Shooting Film in a Digital Era

Shooting Film in a Digital Era

I’ve always been a film guy. I cut my teeth on 16mm. My first child was an Arri 16SRII for which I traveled to the factory in Munich factory 30 years ago to take the delivery. At the National Geographic, that’s all we shot, day in and day out, and there was something reassuring about it: we could hear the film and sprockets chugging away, and we knew we were recording images. With our many years of experience, we had absolute confidence in what those images actually were.

This month I’ve been shooting second unit camera for Moonrise Kingdom, directed by my old friend Wes Anderson. Wes and I date back to the pre-Bottle Rocket days, when I used to shoot commercials and industrial films for Owen Wilson’s dad in Dallas. In those days the film medium was all we had if we really wanted to make a movie. The digital thing was still at least a decade away for serious filmmakers.

Which is why this shoot for me on Super 16 was like a breath of fresh air. The S16mm camera strapped to the underbelly of a 270-horsepower Cessna seaplane would be challenging enough for any imaging system, given the physical stress and massive volume of water pouring back over the lens on take-off. Employing a digital camera however in this setup would be sheer folly, given the force and volume of water and the tight waterproofing required to protect the camera from the massive assault. A modern digital cinema given its thermal characteristics would likely not be able to sustain the heat buildup inside many layers of water-tight plastic – without substantial re-engineering with respect to the camera’s cooling fan and concomitant changes in the aerodynamics of the aircraft.

Here the simplicity and reliability of perforated film chugging over sprockets made the most sense, as the film camera was clearly the right tool for the job. The versatility and latitude of the Vision 3 7213 film proved to be just as critical; the lighting conditions aloft changing dramatically as we darted in and out of the thick clouds of an approaching storm.

Seeing Red in 3D Quality Control

Seeing Red in 3D Quality Control

Comfortable 3D viewing requires matching left and right eye photography. The QC session can help identify obvious faults.

I recently spent a morning at Technicolor’s 3D quality control lab in Glendale CA and was extremely impressed with the sophistication of the QC teams and the review process. Graphical software developed by Technicolor enables the QC operator to accurately assess hyper-divergent and hyper-convergent scenes. No remedial action is performed at this point; the process is solely intended for informational purposes, to alert the filmmaker of potential problems that might impact the viewer’s comfort and overall experience.

Only four pixels of vertical disparity will pass muster in the QC suite so left and right cameras with even the slightest mismatched geometry are readily identified. Color discrapancies and synchronization issues affecting the left and right eye are also easily spotted and flagged. Truth is, under this level of scrutiny, virtually every 3D project ever produced, regardless of budget, will return a bevy of red trouble flags.

The filmmaker’s challenge then is to somehow separate the redness of the QC report from his or her legitimate storytelling goals. The creative requirements of visual storytelling in the third dimension necessarily precludes following too closely the dicates of the QC session. Producers may look upon the report’s red areas, a hyperdiverged background, for instance, in the corner of a scene, and lambaste the stereographer, director and DP, but is this “fault” so identified in the QC report really a defect that will detract from the viewing experience?

Let’s keep in mind that story above all must drive the technology, not the other way around. Audiences do not determine their like or dislike for a 3D program based on the green versus red ratio in a QC report. Yes, the report can be extremely useful to identify clearly disturbing 3D conditions, but it should serve as gospel to compel changes in the storytellers’ creative choices.

My One-Day Vacation

My One-Day Vacation

This entry doesn’t have much to do with the digital craft or video storytelling, although in a way it has everything to do with it. Today I’m in Wales fetching a 1937 Raleigh Roadster with a three-speed Sturmey-Archer and 28 X 1.5-in tires. When this cycle was manufactured in Nottingham two years before the outbreak of World War II there was little about it that one of average or sub-par intelligence couldn’t understand. After all this elegant machine is the quintessential mechanical device with rod-actuated brakes; the three-speed internal gearing integrated into the rear hub operated by a a push-pull cable engaging the planetary gears.

We lived in a mechanical world then, and when something went wrong with the Raleigh Roadster, it was a simple fix – easy to figure out, and easy to remedy. On the other hand, today it accomplishes little to break open a DVD player’s case and stare down a microprocessor. Troubleshooting in the digital era requires insight and understanding of theory, bits and bytes. That takes training and discipline and ongoing study.

So today I am thankful and grateful: my latest cycle acquisition is blessedly devoid of the digital complexity that defines our time.

Greetings from Zanzibar

Greetings from Zanzibar

The East African community is awash with fabulous stories itching to be told, and that’s certainly been my impression this week as I’ve led a camera storytelling workshop here at the Zanzibar International Film Festival (ZIFF) running through 26 June 2011. Many times I’ve said that I always receive far more from my overseas workshops than I give in return; the local filmmakers being so grateful for the guidance and insight that I can provide them.

I have noticed however an interesting paradox among the filmmakers pitching their documentary ideas during this morning’s pitching sessions. First, there was the preponderance of misery-themed proposals: the poisoning of a river at a copper mine in Zambia, a massacre of villagers in Kenya in 1926; the rise to power of a warmonger in the Sudan. For Westerners these subjects while interesting hold diminishing appeal; indeed much of the world has grown weary of the near constant tales of woe and despair across the Dark Continent.

I am far more interested in the countless little stories here in Zanzibar and in the rest of Tanzania that far better illuminate the nature of daily life in this part of the world. Several recent polls of the world’s people have consistently shown East Africans to be among the happiest people on earth, far happier, for example, than the Swedes, the French, or the Canadians. Some things are definitely going right about the quality and character of life here, and I for one am dying to see more of those stories, and less of the disease, depravity and colonial victimization subjects that seem to be so dominant among many of the filmmakers.

It will be very interesting to see the finished productions on Sunday night, and see if I’ve had any noticeable impact on the filmmakers in my workshop, not only from the perspective of raw skills and craft, but also from the point of view of the choice of subject matter itself.

Spreading the Wealth of 3D Knowledge

Spreading the Wealth of 3D Knowledge

It isn’t too often that I am able to offer a 3D camera workshop at a local community college. And this is a pity, for too often we teachers of the video storytelling craft are overly consumed with the name-brand schools, you know, the high-profile institutions that garner most of the headlines and prestige. You can blame the camera manufacturers for much of this; the prospect of significant sales in these wealthy institutions being foremost in their minds.

Still, we trainers are also partly to blame for not doing quite enough to better advertise our wealth of knowledge and enthusiasm. My June 3D workshops at Palomar College in San Marcos CA convinced me that 3D production can be just as relevant and motivational to students at more modest educational institutions. Without exception my Palomar students demonstrated the utmost willingness to take the risks necessary to excel in the new and exciting 3D arena.

To be clear we’re not necessarily talking about aspiring feature filmmakers here. Indeed I am convinced the future of 3D will be predominantly in the non-theatrical arena – in corporate, industrial, wedding and events, and education.

Thus the importance of 3D evangelists and instructors around the world to reach out to all students regardless of economic standing. The skills and confidence gained from the 3D workshop will serve them well, as the jobs and projects of the future will increasingly require an understanding of stereo principals for efficient image capture and post-production.

I welcome the opportunity to offer my knowledge and training to a wide cross section of students all over the world. As I write this I am en route to Tanzania to lead a camera workshop next week at the Zanzibar International Film Festival . While my students will no doubt learn a wide range of skills to enhance their visual storytelling I also know that I will receive far greater inspiration in return; these East African filmmakers and camera people serving up their own remarkable stories reflecting their unique experiences and insights.

http://www.ziff.or.tz/news/high-definition-workshop-barry-braverman-ziff

Engineers & Post Wonks: Take a Hike!

Engineers & Post Wonks: Take a Hike!

This month I had the opportunity to lead a two-day Panasonic/DirecTV-sponsored workshop in connection with a national 3D student movie making contest. I also led a longer (five-day) student workshop in Mumbai in February that was vastly different in tone and scope. The Indian sessions featured almost three days of teaching story development skills, a critical training component invariably omitted by the overzealous technical wonks.

I’ve been saying for years that we trainers of the video craft place far too much emphasis on the technical minutiae and too little on story and the emotional component, which are after all the only thing an audience truly cares about. Unfortunately the tech heads raised their ugly heads once again in the three days ahead of my Los Angeles workshps at DirecTV. An “expert” from one of Hollywood’s foremost tech houses had apparently urged may students to adopt the so-called French system of shooting 3D, known as Le Méthode Dérobé.

The method stipulates that the background divergence of a scene must be fixed at the maximum percentage specified by the broadcaster, and that we should only vary the camera’s interaxial distance to set the desired convergence angle. Since the Panasonic AG-3DA1 has a fixed IA of 60mm, this means, according to this expert, that the camera must be placed at precisely 9.5 feet (about 3m) to avoid unacceptable hyper-divergence.

As my students struggled through their storyboards, it was obvious that maintaining a fixed 9.5 foot camera distance was impractical, that adopting such a restrictive approach would severely detract from the effectiveness of the students’ visual stories.

The fact is, given the limitations of the camera’s fixed IA, the 3DA1 shooter must be mindful of potential hyper-divergence, too close objects, the impact of focal length on object roundness, and, of course, the intended size of the 3D display screen. These matters are integral to shooting 3D in any form, but are especially critical when shooting with the 3DA1, given the inherent limitations of a fixed binocular-lens system.

Why Micro Four-Thirds Makes Sense

Why Micro Four-Thirds Makes Sense

One of the reasons frequently cited for the current fad among shooters demanding larger and higher K cameras is this little matter of depth-of-field. Advocates for battleship-size imagers in cameras claim that a narrow depth of field is essential to producing first-class work, and that no self-respecting shooter would be caught dead shooting with a – oh God, no, heaven forbid — a 1/3-inch traditional camcorder. Never mind that one’s choice of optics is far more important; indeed one’s choice of lens can account for most of the professionalism that an audience can perceive on screen. Sure the RED and the DSLR craze has propagated this notion that bigger must be better; do I have to remind you that this “bigger” mentality has prevailed among many races of men since time immemorial?

When it comes to imager size in professional video cameras I would assert that quite the reverse is often true. If you’re shooting 3D we WANT as much depth of field as we can muster, which gives the smaller imager in a camera, say, 1/3-in to 2/3-in, a significant advantage. Likewise if we’re shooting wildlife in Tanzania we usually prefer increased depth of field to compensate for the focal length lenses we tend to use.

On the other hand when a shallower depth of field is legitimately demanded, the Micro Four-Thirds format championed by Panasonic and Olympus provides an optimal solution. The 22.5 mm diagonal offers the inherently shallow focus for narrative-type shows, as conditioned over many years by our collective 35mm cine experience. This desirable range of focus is much more readily and practically achievable in the MFT format, without the peril of the nose in-focus/eyes out-of-focus syndrome that plagues users of the Canon 5D for example.

My point here is that craft rules the roost, or at least it ought to; a larger imager with more Ks is NOT better, unless your particular brand of storytelling demands such a treatment. And inasmuch as larger imagers demand proportionately better optics, it simply means we should determine our camera and imager size needs according to the quality of optics we have at hand.

And keep in mind this one inescapable fact: If you’re planning to use a consumer still lens, regardless of your camera’s sensor size or resolution, you can only attain consumer grade images! Think about it.